AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Current state of food security: Sources and solutions

|

Copyright: Isaac Holliss

|

Description: What is food security? What makes global food insecurity and how can it be overcome?

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

Current state of food security: Sources and solutions

|

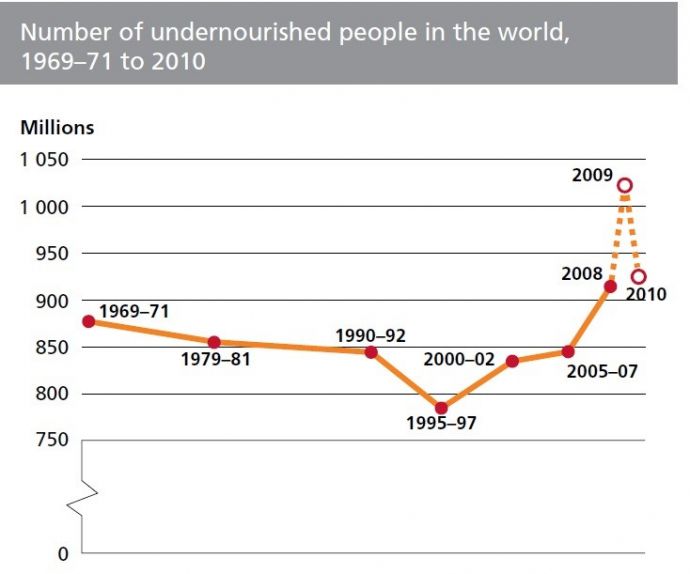

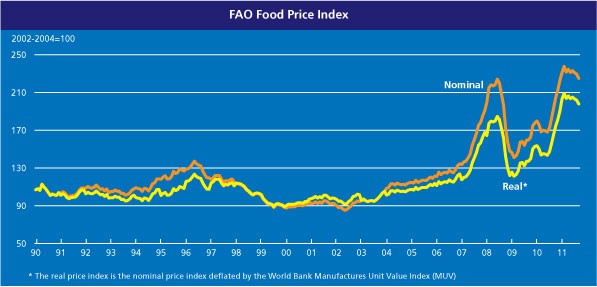

Introduction Food security in the modern world is characterised by a sobering puzzle; 1.5 billion people are overweight and obese while 925 million are malnourished.[1] Similarly, there are now 42 million obese children under the age of five, while nearly 5 million children die of malnutrition-related illnesses every year.[2] The concept of food security lies at the nexus of a complex web of issues; the international trading system, agricultural yields, natural disasters, political conflict, and poverty. I discuss how best to define food security, I examine the state of food insecurity in the world today, and I identify three causes of food insecurity: financial, physical, and political. I then turn to current efforts to address food insecurity, with particular focus on the role of international organisations. Having surveyed current efforts, I suggest three alternate policy options for improving the international community’s response. Defining food security Defined in its most general sense, food security represents someone having access to enough food to lead a healthy lifestyle. This definition begs a number of questions; how much is ‘enough’? Whose access matters – the individual’s, the household’s, or the country’s? Is there truly ‘access’ to food if it is unaffordable for much of the population? These questions necessarily lead us to narrow the definition, and here I will use the definition adopted at the 1996 World Food Summit: ‘Food security exists when all people, at all times, have physical and economic access to sufficient safe and nutritious food that meets their dietary needs and food preferences for an active and healthy life.’[3] The Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) identifies four key components of food security: There must be sufficient food physically available; it must be accessible in terms of price and physical collection; the food must supply sufficient nutrients for the body in order to lead a healthy lifestyle; and the preceding components must be stable over time.[4] One readily identified problem with the definition above is the concept that food security involves an active and healthy lifestyle. If adequate nutrition is the goal, then simply ensuring access to food is insufficient. Access to clean water, sanitary conditions, and health care are all necessary to transform food into a healthy lifestyle.[5] Food insecurity exists in the absence of one or more of the above components. The current state of food security The issue of food security is one of the most potent human security issues of our time. The East African drought afflicting the Horn of Africa has resulted in 12 million people requiring emergency assistance, with up to 750,000 people at risk of dying in the next four months without urgent food aid.[6] The Somali famine is a catastrophe of shocking proportions, but it is not the only region in the world to be suffering from chronic food insecurity. Chronic undernourishment is currently experienced in as many as 10 countries in Africa,[7] and a further 578 million people remain undernourished in Asia.[8] Global hunger figures are sobering; 925 million people were undernourished in 2010, and 22 countries are classified as being in a ‘protracted crisis’ of more than seven years.[9] Although food insecurity has traditionally been viewed as a humanitarian concern, it has the potential to create political instability. Food riots in 2008 destabilised a number of governments.[10] More recently, the East African Drought has driven 1,400 refugees per day from Somalia into its neighbour, Kenya, stretching the resources of its government.[11] The Arab Spring, a series of popular uprisings across the Middle East and North Africa in 2011, was itself partly driven by rising food prices.[12] Current food security efforts: The role of international organisations Food security is a field which is dominated by international organisations. The largest of these are the FAO and the World Food Programme (WFP). The former focuses its efforts on improving worldwide nutrition and agricultural productivity, the latter is a specialist in delivering emergency food aid.[13] The Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR) is an umbrella organisation for a collection of government supported agricultural research institutes around the world.[14] The International Fund for Agricultural Development (IFAD) is a specialised agency within the UN system and focuses on reducing poverty and hunger in the rural areas of developing countries.[15] Other international organisations also have an interest in food security: the World Bank funds research into improving agricultural productivity and supports projects aimed at improving access to rural areas;[16] the UN Development Programme aims to reduce poverty;[17] and UNICEF seeks to reduce suffering by children worldwide.[18] In 2008 the High-Level Task Force on the Global Food Crisis (HLTF) was formed by the leaders of a number of UN agencies, and its mandate was to produce a Comprehensive Framework for Action to address food insecurity resulting from the high food prices of 2008-9.[19] Causes of food insecurity Financial The financial cause of food insecurity has two dimensions; poverty, and the price of food. Poverty and food security share a strong correlation; poverty causes an inability to purchase food, and limits a country’s ability to invest in enhanced food production, creating a self-reinforcing cycle. In similar fashion, spikes in the international price of food can be the difference between a household being able to afford to buy food, and hence be food secure, or not being able to afford sufficient food. The FAO’s Food Price Index indicates that prices spiked in 2007-8 and again in 2010-11, hitting an all-time high in February 2011.[20] Figure 1 below illustrates the clear link between food prices and malnutrition.

Figure 1 – The correlation between food prices and undernourishment.[21]

There are two driving forces behind the recent rise in food prices: the increasing proportion of crops used to produce biofuel; and rising demand from emerging economies. The extent of the impact of increasing biofuel production remains disputed – an unreleased World Bank report suggested their use has forced global food prices upwards by 75 per cent in recent years, whereas the US government argues it contributes only three per cent.[22] Even small increases can have significant effects on poverty levels; a ten per cent rise in the price of food raises poverty in developing countries by 0.4 per cent.[23] The growing middle-class in India and China has resulted in a rapid increase in the demand for greater quantities of food, and meat products in particular. The increasing demand for meat is particularly relevant as it takes ten times the resources to produce one gram of meat protein than it does one gram of vegetable protein.[24] As incomes continue to increase in the developing world there will be increased pressure on food prices. Also significant is the fact that up to 90 per cent of the world’s grain trade is controlled by only three trading companies; ADM, Bunge, and Cargill.[25] The high concentration of grain supplies in a small number of firms raises the risk of price fixing, and the possibility that these firms may manage the supply of grain in order to maximise profits, a goal at odds with improving access for their customers. Natural Natural disasters and extreme weather events are often direct causes of food insecurity. Drought is the underlying cause of the ongoing famine in East Africa; the lowest levels of seasonal rain since 1950 have triggered widespread crop failure, livestock mortality, and hence high prices for food.[26] Other natural disasters also impact food security; in 2010 fires from an extreme heatwave destroyed nearly one fifth of Russia’s grain crops, and Russia’s subsequent ban on grain exports was credited with pushing up the global price of grain by up to a third.[27] Price increases affect developing countries the most; recent price surges have threatened to place millions into poverty, because those in developing countries spend a higher proportion of their income on basic foodstuffs; over 50 per cent in East Africa, compared to eight per cent in North America.[28] Climate change will play an increasingly important role in food security as world temperatures continue to rise. Some research has shown that for every one degree (Celsius) increase in world temperatures, agricultural yields fall by 10 per cent; a sobering proposition given that the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) expects temperatures to rise by between 1.4-5.8 degrees in the coming century.[29] Climate change is likely to exacerbate two agricultural challenges in particular; falling water tables, and declining productivity growth.[30] Water security and food security are intrinsically linked; it takes 1000 tons of water to produce one ton of grain, and nearly ten times as much for meat. [31] Agriculture will be uniquely affected by climate change, and this is significant for two reasons: agriculture represents the world’s principal source of food; and it represents the main source of income for 36 per cent of the world’s workforce, or two thirds of the workforce in sub-Saharan Africa.[32] Climate change is likely to increase the number of extreme weather events. In fact, this trend has already begun; on average around 500 weather-related disasters occur annually throughout the world, an increase from an average of only 120 in the 1980s.[33] In this way, climate change does not simply affect the quantity of food available, it also affects the the roads, storage, and other infrastructure involved in transporting food around the globe.[34] It is expected that climate change will increase the number of malnourished people by between 35 and 170 million by 2080.[35] Political Military conflict, political instability, and economic embargos can all create food insecurity or exacerbate the effect of natural disasters. Armed conflict in the Horn of Africa has physically disrupted farming activities, decreasing the region’s ability to produce food. The civil war in Somalia caused its food production to drop by a third between 1989 and 1992, and even now it has failed to return to pre-civil war levels.[36] In Libya, the civil war which engulfed the country in 2011 had the dual effect of disrupting local farming activities and restricting imports of food through its ports.[37] In some cases, however, political factors serve to exacerbate an already poor situation. Civil war, insurgencies, and armed conflict in general can hamper the delivery of emergency food assistance to where it is most needed. In Somalia, particularly the areas controlled by rebel group al-Shabab, the supply of emergency relief to those in most need is limited.[38] Embargos imposed for political reasons may also result in food insecurity by increasing poverty. For instance, the international embargo imposed on central and southern Iraq in the 1990s coincided with a vastly increased malnutrition rate among those regions’ children from 9.2 per cent in 1991 to 25 per cent in 1997, as compared to a reduction in child malnutrition in the Kurdish north where the embargo was relaxed.[39] Addressing food insecurity In this section I examine three alternate approaches to addressing food security: a realist, or state-security approach; a liberal-institutionalist approach; and a ‘third way’ with elements of both. Realist approach Since food security is closely linked to physical security, food insecurity should be considered a security threat in the traditional sense. To view the high correlation between food insecurity and physical insecurity one only has to examine the food riots in 2008, and the role played by rising food places in instability in the Middle East and North Africa. Furthermore, it is clear that in many of the world’s worst food security situations, it is a poor security environment which is causing or exacerbating food insecurity. In Somalia, the on-going civil war has disrupted normal agricultural activities, exacerbating the effects of the drought, and the militant group al-Shabab has hindered the delivery of sufficient international aid.[40] A number of policy prescriptions stem from linking food security with physical security. First, more emphasis should be placed on ensuring secure access to food supplies. Humanitarian food relief efforts should be free to deliver assistance wherever it is needed without threats to the deliverers’ safety. In many cases, this will entail accompanying food relief with a military escort force. Such a concept has precedent; in 1992, Security Council Resolution 794 authorised ‘all necessary means to establish…a secure environment for humanitarian relief operations in Somalia.’[41] In this example, the US provided the security forces necessary to force the warring Somali warlords to accept foreign assistance, and to ensure that assistance could be safely delivered.[42] In 2008 France invoked the ‘responsibility to protect’ doctrine in its failed attempt to persuade the international community to use force to provide humanitarian assistance to Myanmar’s worst hit areas after Cyclone Nargis.[43] Second, threats to food security should be considered threats to conventional security. The Security Council is structured to focus its efforts on security threats. By considering food security as a conventional security threat, the topic will be placed higher in the agenda. States have traditionally proven to be more likely to act in order to address security threats than they are with other threats; witness the US response to 9/11 and compare it with its lacklustre response to climate change. Considering food security as a conventional security threat poses a risk that food will become militarised. Oil is considered a strategic good, and this has led to tensions between states seeking to secure their future energy supplies. In 2005 a Chinese state-owned oil company attempted to buy US oil giant Unocal, but was blocked by US politicians concerned at its strategic implications.[44] States will act to secure their food supply, just as they are acting increasingly to ensure their energy supplies. There are examples that this is already occurring; Chinese companies’ are increasingly attempting to purchase farmland in NZ.[45] Neo-liberal institutionalist approach Food security requires a high-level coordinating body that is able to better coordinate the international community’s current response to food insecurity. Inter-governmental organisations ‘can provide information, reduce transaction costs, make commitments more credible, [and] establish focal points for coordination’.[46] For this reason, a new institution able to coordinate the entire UN food security effort has the potential to tie together government and inter-governmental efforts. An analogous organisation exists for both refugees and human rights; the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights is a coordinating body for the all of the UN agencies with policies which touch upon human rights. A similar body exists for refugees called the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees. The issue of food security is important enough to warrant its own coordinating agency. Figure 2 provides an overview of the number of agencies dealing with food security issues. Without a single coordinating policy, the large number of UN agencies dealing with food security risk overlap and duplication in resources, policy, and reporting. The creation of an ‘Office of the High Commissioner for Food Security’ (OHCFS) as the coordinating organisation for the UN’s food security policies would eliminate this risk by dedicating itself to coordinating these organisations’ activities. This will improve the use of these organisations’ funding and manpower and their ability to produce meaningful change for those suffering from food insecurity.

Figure 2 – A survey of the major UN agencies with policies affecting food security. Although the HLTF created in 2008 represented a step in the right direction by signalling greater cooperation among various food security agencies, it can be criticised in two ways. First, it delegates responsibility for implementing its food security plan to national governments, which poses the risk that the response will become fragmented and be at the mercy of domestic politics. Second, its ability to effect long-term change is limited by its transitory nature; it was created in response to a single crisis and was mandated to produce a report to address that crisis, with only a small secretariat to ‘provide logistical support’ to the HLTF, reducing its future footprint.[47] A ‘third way’: Research and development Greater collaborative research between governments has the potential to produce another ‘green revolution’ which may improve agricultural yields and lower food prices. The ‘Green Revolution’ that occurred between the 1940s and the 1980s transformed food production and helped support rapid growth in the world’s population. The revolution was a series of technological and ‘best-practice’ enhancements to the agriculture industry and was particularly effective in improving agricultural yields in Asia and India.[48] Improved use of irrigation and fertilizers, combined with cross-breeding plants to increase their resistance to famine and disease, helped to boost agricultural yields across the globe. Productivity growth has now dropped to 0.5 per cent from an average of 2.1 per cent during the revolution.[49] I argue that applying more resources to agricultural research has the potential to create a new green revolution. The return on investments into agricultural yield improvements can be substantial, meaning the commercial case is already made. CGIAR estimates that its research conducted since 1989 has resulted in improved economic benefit of $14 billion for grain crops, achieving this with less than $7 billion of funding.[50] Without its research, world food production would be up to 5% lower, and grain prices more than 20% higher.[51] CGIAR allows states to cooperate in a manner which benefits all donors, is transparent, and low-cost. At the same time, it recognises that states are the actors with the necessary resources to produce meaningful change. Another option is to pursue a ‘gene revolution’ whereby states relax their restrictions on genetically engineered (GE) crops and boost funding for their research in order to produce new varieties of drought- and disease- resistance plants. The norm of anti-GE crops is widespread and remains a key plank of Greenpeace’s ideology, representing an NGO with one of the world’s largest memberships.[52] States need to place more emphasis on building public confidence in GE conducting research that demonstrates its benefits, while it develops safeguards that address the potential risks. GE presents the agricultural industry with new methods by which it can increase its yields; for instance by improving plants’ resistance to diseases and pests, by improving their interaction with pesticides, and by improving their nutritional value.[53] Conclusion: The future of food security Food insecurity is one of the most pressing issues with which modern policymakers must grapple. Although the Green Revolution vastly improved food security for millions worldwide, it lulled many into the false sense of security that food would continue to be available cheaply for many years to come. Spikes in the price of basic foodstuffs in recent years have reignited Malthusian concerns over the availability of food to meet the needs of the world’s growing population. Demand is growing rapidly as the middle class in emerging economies consume greater quantities of food, and meat in particular. Current efforts to improve food security are well-intentioned but poorly coordinated, creating wasteful overlap between UN agencies and research programmes. A realist response to food security would see the issue considered as a traditional security threat, and this perspective may place greater pressure on the world’s major powers to intervene in humanitarian disasters. A neo-liberal institutionalist approach would see greater authority placed in the hands of a new international organisation which has the potential to provide greater focus to global food security efforts. I argue that the most effective policy is a second green revolution, or a ‘gene revolution’ through greater use of GE crops. States must place greater emphasis on cooperating to address food insecurity; otherwise the issue risks fuelling conflict and damaging economic growth, to say nothing of the humanitarian imperatives.

Bibliography Bailey, Robert. ‘Growing a Better Future: Food justice in a resource-constrained world.’ May, 2011. Report available at: http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/growing-a-better-future-food-justice-in-a-resource-constrained-world-132373 (accessed October 7, 2011). Balmforth, Tom. ‘Russian grain export ban starts, Telegraph, August 15, 2010. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/7946850/Russian-grain-export-ban-starts.html (accessed October 7, 2011). BBC News. ‘Child death rate doubles in Iraq.’ May 25, 2000. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/763824.stm (accessed October 7, 2011). Bennett, Adam. ‘Chinese want to buy $1.5b NZ dairy empire.’ NZ Herald, March 25, 2010. http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10634177 (accessed October 7, 2011). Bilefsky, Dan. ‘U.N. Secretary General Expresses New Alarm Over Libya Strife.’ New York Times, March 24, 2011. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/24/world/africa/25nations.html (accessed October 7, 2011). Borger, Julian. ‘Feed the World? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits.’ The Guardian, February 26, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/feb/26/food.unitednations (accessed October 7, 2011). Brown, Lester R. Outgrowing the Earth: The Food Security Challenge in an Age of Falling Water Tables and Rising Temperatures. New York: Earth Policy Institute, 2004. CGIAR. ‘Research and Impact.’ http://www.cgiar.org/impact/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). CGIAR. ‘Who We Are.’ http://cgiar.org/who/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). CGIAR. ‘Who We Are: Donors and Funding.’ http://cgiar.org/who/members/funding.html (accessed October 7, 2011). Chakrabortty, Aditya. ‘Secret report: biofuel caused food crisis.’ The Guardian, July 3, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/jul/03/biofuels.renewableenergy (accessed October 7, 2011). Chothia, Farouk. ‘Could Somali famine deal a fatal blow to al-Shabab?’ BBC News, August 9, 2011. http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14373264 (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security.’ Report available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/al936e/al936e00.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘Climate Change and Food Security: A Framework Document.’ Rome, 2008. Rreport available at http://www.fao.org/forestry/15538-079b31d45081fe9c3dbc6ff34de4807e4.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘FAO Food Price Index. http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘FAO’s mandate.’ http://www.fao.org/about/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘ISFP and the UN High-level Task Force on the Food Security Crisis.’ http://www.fao.org/isfp/isfp-and-the-un-high-level-task-force-on-the-food-security-crisis/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). FAO. ‘The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Address food insecurity in protracted crises.’ Rome, 2010. Available at: http://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). FEWS. ‘Eastern Africa: Drought – Humanitarian Snapshot.’ http://www.fews.net/docs/Publications/Horn_of_Africa_Drought_2011_06.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). Gorst, Isabel. ‘Russian Grain Ban Angers Traders.’ Financial Times, August 15, 2010. http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/4a47ed9a-a898-11df-86dd-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Y3WPqUqC (accessed October 7, 2011). Greenpeace (India). ‘Threatening levels of Chemical fertilisers in Punjab groundwater: Greenpeace study.’ Press release, November 26, 2009. http://www.greenpeace.org/india/en/news/threatening-levels-of-chemical/ (accessed October 7, 2011). Greenpeace (International). ‘What’s wrong with genetic engineering (GE)?’ http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/agriculture/problem/genetic-engineering/ (accessed October 7, 2011). High-Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis. ‘Outcomes and Actions for Global Food Security: Excerpts from ‘Comprehensive Framework for Action.’ July 2008. Available at: http://www.un.org/issues/food/taskforce/pdf/OutcomesAndActionsBooklet_v9.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). IFAD. ‘About IFAD.’ http://www.ifad.org/governance/index.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). Indexmundi. ‘Somalia – food production index.’ http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/somalia/food-production-index (accessed October 7, 2011). Ivanic, Maros, and Will Martin. ‘Implications of Higher Global Food Prices for Poverty in Low-Income Countries.’ World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4549. http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2008/04/16/000158349_20080416103709/Rendered/PDF/wps4594.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). Keohane, Robert O., and Lisa L. Martin. ‘The Promise of Institutionalist Theory.’ International Security 20, no.1 (1995): 39-51. Koning, Niek, and Arthur P.J. Mol. ‘Wanted: institutions for balancing global food and energy markets.’ Food Security 1 (2009):291-303. Ludi, Eva. ‘Climate change, water and food security.’ Overseas Development Institute Background Note, March 2009. Available at: http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/3148.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). Manning, Richard. Food’s Frontier: The Next Green Revolution. New York: North Point Press, 2000. Mydans, Seth. ‘Myanmar Faces Pressure to Allow Major Aid Effort.’ New York Times, May 8, 2008. http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/08/world/asia/08myanmar (accessed October 7, 2011). Pinstrup-Anderson, Per. ‘Food security: definition and measurement.’ Food Security 1 (2009): 5-7. Renewable Fuels Agency (United Kingdom). ‘The Gallagher Review of the indirect effects of biofuels production.’ July 2008. Report available at: http://www.bioenergy.org.nz/documents/liquidbiofuels/Report_of_the_Gallagher_review.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). Rice, Xan. ‘Somali refugees fight cholera and measles as hunger spreads.’ Guardian, August 13, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/aug/13/somali-refugees-kenya-ethiopia-epidemic (accessed October 7, 2011). Tran, Mark. ‘UN declares sixth famine zone in Somalia.’ The Guardian, September 5, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2011/sep/05/famine-somalia-crisis-deepens (accessed October 7, 2011). UNDP. ‘Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of National: Pathways to Human Development.’ 2010. Report available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2010_EN_Complete_reprint.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). UNICEF. ‘Child malnutrition prevalent in central/south Iraq.’ http://www.unicef.org/newsline/prgva11.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). UNICEF. ‘How we work.’ http://www.unicef.org/whatwedo/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations. ‘Somalia – UNOSOM I.’ Last updated March 21, 1997. http://www.un.org/Depts/DPKO/Missions/unosomi.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). United Nations Security Council. ‘Security Council Resolutions – Resolution 794 (1992).’ http://www.un.org/documents/sc/res/1992/scres92.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). United Nations. ‘The Secretary-General’s High-Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis: Terms of Reference.’ http://www.un.org/issues/food/taskforce/tor.shtml (accessed October 7, 2011). WFP. ‘Hunger Map 2011.’ Info graphic. http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp229328.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). WFP. ‘Hunger: Hunger Stats.’ http://www.wfp.org/hunger/stats (accessed October 7, 2011). White, Ben. ‘Chinese Drop Bid To Buy U.S. Oil Firm.’ Washington Post, August 3, 2005. http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/02/AR2005080200404.html (accessed October 7, 2011). WHO ‘Obesity and overweight.’ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). WHO. ‘Childhood overweight and obesity.’ http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011) WHO. ‘Who are the hungry?’ http://www.wfp.org/hunger/who-are (accessed October 7, 2011). Wu, Felicia. The future of genetically modified crops: lessons from the Green Revolution. Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2004. Zurayk, Rami. ‘Use your loaf: why food prices were crucial in the Arab spring.’ The Guardian, July 17, 2011. http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/17/bread-food-arab-spring (accessed October 7, 2011). Zurayk, Rami. ‘Use your loaf: why food prices were crucial in the Arab spring.’ The Guardian, July 17, 2008. http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/17/bread-food-arab-spring (accessed October 7, 2011).

[1] World Health Organization, ‘Obesity and overweight,’ http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs311/en/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011); and WHO, ‘Who are the hungry?’ http://www.wfp.org/hunger/who-are (accessed October 7, 2011). [2] WHO, ‘Childhood overweight and obesity,’ http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/childhood/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011); and World Food Programme, ‘Hunger: Hunger Stats,’ http://www.wfp.org/hunger/stats (accessed October 7, 2011). [3] Food and Agriculture Organization, ‘An Introduction to the Basic Concepts of Food Security,’ 1, report available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/013/al936e/al936e00.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [4] Ibid. [5] Per Pinstrup-Anderson, ‘Food security: definition and measurement,’ Food Security 1 (2009): 6. [6] Mark Tran, ‘UN declares sixth famine zone in Somalia,’ Guardian, September 5, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/global-development/2011/sep/05/famine-somalia-crisis-deepens (accessed October 7, 2011). [7] WFP, ‘Hunger Map 2011,’ Info Graphic, http://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp229328.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [8] FAO, ‘The State of Food Insecurity in the World: Address food insecurity in protracted crises,’ (Rome, 2010), 10, report available at: http://www.fao.org/publications/sofi/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). [9] Ibid., 8 and 12. [10] Julian Borger, ‘Feed the World? We are fighting a losing battle, UN admits,’ The Guardian, February 26, 2008, http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/feb/26/food.unitednations (accessed October 7, 2011). [11] Xan Rice, ‘Somali refugees fight cholera and measles as hunger spreads,’ Guardian, August 13, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2011/aug/13/somali-refugees-kenya-ethiopia-epidemic (accessed October 7, 2011). [12] Rami Zurayk, ‘Use your loaf: why food prices were crucial in the Arab spring,’ The Guardian, July 17, 2011, http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/17/bread-food-arab-spring (accessed October 7, 2011). [13] FAO, ‘FAO’s mandate,’ http://www.fao.org/about/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). [14] CGIAR, ‘Who We Are,’ http://cgiar.org/who/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [15] International Fund for Agricultural Development, ‘About IFAD,’ http://www.ifad.org/governance/index.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). [16] CGIAR, ‘Who We Are: Donors and Funding,’ http://cgiar.org/who/members/funding.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [17] UNDP. ‘Human Development Report 2010: The Real Wealth of National: Pathways to Human Development,’ (2010), 94, report available at: http://hdr.undp.org/en/media/HDR_2010_EN_Complete_reprint.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [18] United Nations Children’s Fund, ‘How we work,’ http://www.unicef.org/whatwedo/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [19] High-Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis, ‘Outcomes and Actions for Global Food Security: Excerpts from ‘Comprehensive Framework for Action’, July 2008, 2, report available at: http://www.un.org/issues/food/taskforce/pdf/OutcomesAndActionsBooklet_v9.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [20] FAO, ‘FAO Food Price Index,’ http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). [21] FAO, ‘The State of Food Insecurity in the World,’ 9; and FAO, ‘FAO Food Price Index,’ http://www.fao.org/worldfoodsituation/wfs-home/foodpricesindex/en/ (accessed October 7, 2011). [22] Aditya Chakrabortty, ‘Secret report: biofuel caused food crisis,’ Guardian, July 3, 2008, http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2008/jul/03/biofuels.renewableenergy (accessed October 7, 2011); and Renewable Fuels Agency (United Kingdom), ‘The Gallagher Review of the indirect effects of biofuels production,’ July 2008, 59, report available at: http://www.bioenergy.org.nz/documents/liquidbiofuels/Report_of_the_Gallagher_review.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). For a general discussion on the role of biofuels in raising the price of food, see Niek Koning, and Arthur P.J. Mol, ‘Wanted: institutions for balancing global food and energy markets,’ Food Security 1 (2009): 291-295. [23] Maros Ivanic, and Will Martin, ‘Implications of Higher Global Food Prices for Poverty in Low-Income Countries,’ World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 4549, 47, http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2008/04/16/000158349_20080416103709/Rendered/PDF/wps4594.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [24] Richard Manning, Food’s Frontier: The Next Green Revolution (New York: North Point Press, 2000), 82. [25] Rami Zurayk, ‘Use your loaf: why food prices were crucial in the Arab spring,’ Guardian, July 17, 2008, http://www.guardian.co.uk/lifeandstyle/2011/jul/17/bread-food-arab-spring (accessed October 7, 2011). [26] FEWS, ‘Eastern Africa: Drought – Humanitarian Snapshot,’ http://www.fews.net/docs/Publications/Horn_of_Africa_Drought_2011_06.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [27] Isabel Gorst, ‘Russian Grain Ban Angers Traders,’ Financial Times, August 15, 2010, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/4a47ed9a-a898-11df-86dd-00144feabdc0.html#axzz1Y3WPqUqC (accessed October 7, 2011); and Tom Balmforth, ‘Russian grain export ban starts,’ Telegraph, August 15, 2010, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/russia/7946850/Russian-grain-export-ban-starts.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [28] Robert Bailey, ‘Growing a Better Future: Food justice in a resource-constrained world,’ (May, 2011), 21, report available at: http://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/publications/growing-a-better-future-food-justice-in-a-resource-constrained-world-132373 (accessed October 7, 2011). [29] Lester R. Brown, Outgrowing the Earth: The Food Security Challenge in an Age of Falling Water Tables and Rising Temperatures (New York: Earth Policy Institute, 2004), 11. [30] Ibid., 10. [31] Ibid. [32] FAO, ‘Climate Change and Food Security: A Framework Document,’ (Rome, 2008), 9, report available at http://www.fao.org/forestry/15538-079b31d45081fe9c3dbc6ff34de4807e4.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [33] Ibid., 20. [34] FAO, ‘Climate Change and Food Security,’ 12. [35] Eva Ludi, ‘Climate change, water and food security,’ Overseas Development Institute Background Note, March 2009, 3, available at: http://www.odi.org.uk/resources/download/3148.pdf (accessed October 7, 2011). [36] Indexmundi, ‘Somalia – food production index,’ http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/somalia/food-production-index (accessed October 7, 2011). [37] Dan Bilefsky, ‘U.N. Secretary General Expresses New Alarm Over Libya Strife,’ New York Times, March 24, 2011, http://www.nytimes.com/2011/03/24/world/africa/25nations.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [38] Farouk Chothia, ‘Could Somali famine deal a fatal blow to al-Shabab?’ BBC News, August 9, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14373264 (accessed October 7, 2011). [39] UNICEF, ‘Child malnutrition prevalent in central/south Iraq,’ http://www.unicef.org/newsline/prgva11.htm (accessed October 7, 2011); See also BBC News, ‘Child death rate doubles in Iraq,’ May 25, 2000, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/health/763824.stm (accessed October 7, 2011). [40] Farouk Chothia, ‘Could Somali famine deal a fatal blow to al-Shabab?’ BBC News, August 9, 2011, http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-14373264 (accessed October 7, 2011). [41] United Nations Security Council, ‘Security Council Resolutions – Resolution 794 (1992)’, available at http://www.un.org/documents/sc/res/1992/scres92.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). [42] United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations, ‘Somalia – UNOSOM I,’ last updated March 21, 1997, http://www.un.org/Depts/DPKO/Missions/unosomi.htm (accessed October 7, 2011). [43] Seth Mydans, ‘Myanmar Faces Pressure to Allow Major Aid Effort,’ New York Times, May 8, 2008, http://www.nytimes.com/2008/05/08/world/asia/08myanmar (accessed October 7, 2011). [44] Ben White, ‘Chinese Drop Bid To Buy U.S. Oil Firm,’ Washington Post, August 3, 2005, http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2005/08/02/AR2005080200404.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [45] Adam Bennett, ‘Chinese want to buy $1.5b NZ dairy empire,’ NZ Herald, March 25, 2010, http://www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10634177 (accessed October 7, 2011). [46] Robert O. Keohane, and Lisa L. Martin, ‘The Promise of Institutionalist Theory,’ International Security 20, no.1 (1995): 42. [47] United Nations, ‘The Secretary-General’s High-Level Task Force on the Global Food Security Crisis: Terms of Reference,’ http://www.un.org/issues/food/taskforce/tor.shtml (accessed October 7, 2011). [48] Ibid., 4-5. [49] Ibid., 5. [50] CGIAR, ‘Research and Impact,’ http://www.cgiar.org/impact/index.html (accessed October 7, 2011). [52] Greenpeace (International), ‘What’s wrong with genetic engineering (GE)?’ http://www.greenpeace.org/international/en/campaigns/agriculture/problem/genetic-engineering/ (accessed October 7, 2011). [53] Felicia Wu, The future of genetically modified crops: lessons from the Green Revolution, (Santa Monica: RAND Corporation, 2004), 41-43. |