AWA: Academic Writing at Auckland

Title: Acute on Chronic Cholecystitis Secondary to Cholelithiasis

|

Copyright: Vanessa Ng

|

Description: Description, pathogenesis, and clinical features of cholecystitis and cholelithiasis.

Warning: This paper cannot be copied and used in your own assignment; this is plagiarism. Copied sections will be identified by Turnitin and penalties will apply. Please refer to the University's Academic Integrity resource and policies on Academic Integrity and Copyright.

|

Writing features

|

Acute on Chronic Cholecystitis Secondary to Cholelithiasis

|

Figure 1: Gallbladder specimen from 50 year old woman showing cholecystitis and cholelithiasis Description Gross Features: The specimen in Figure 1 shows a gallbladder with cholecystitis (inflammation) and cholelithiasis (gallstones). The walls of the gallbladder are thick and dilated (1). This gallbladder is 15cm in length, much larger than normal gallbladders. The thickness of the walls is due to the events of acute and chronic inflammation: fibrosis, oedema and the migration of cells (particularly leukocytes) into the tissue. The mucosa shows both tissue necrosis (grey areas) (2) and inflammation (red areas) (3), while the serosa shows congestion (4). The gallbladder contains four white, facetted, cholesterol gallstones (5). Microscopic Features: The gallbladder microscopically consists of mucosa lining the lumen, muscularis propria and an outer serosa or adeventitia (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010). In acute cholecystitis, which may be caused by impaction of gallstones, the gallbladder will histologically show features of acute inflammation: infiltration of neutrophils, oedema and, if severe enough, fractured and featureless necrotic cells of the mucosa (Jessurun & Pambuccian, 2009). If the inflammation continues and is not resolved, signs of chronic inflammation will occur: infiltration of lymphocytes, macrophages, plasma cells and eosinophils, and replacement of necrotic tissue with collagen and granulation tissue (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010). Metaplasia of the epithelium may also occur, with the cells beginning to resemble gastric pyloric or antral cells (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010).

Pathogenesis Cholecystitis, inflammation and bacterial growth in the gallbladder, is usually caused by gallstones obstructing the cystic duct causing acute inflammation and distension, due to the increase in pressure in the lumen (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010). Cholecystitis can also be caused by impaction of gallstones which compresses the cystic artery leading to ischemia and an inflammatory response. In approximately 10% of cases of acute cholecystitis, cholelithiasis is not the cause (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010). This is called alcalculous cholecystitis, and although the pathogenesis is not always clear, patients usually have associated conditions such as diabetes mellitus, trauma or cardiovascular disease (Jessurun & Pambuccian, 2009). The formation of gallstones is particularly relevant as it is the most common cause of cholecystitis. There are three types of gallstones: cholesterol gallstones, as seen in the specimen in Figure 1, comprise 75-90% of all gallstones, black pigment stones and brown pigment stones (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). There are three main factors involved in the formation of cholesterol gallstones: cholesterol supersaturation, nucleating and anti-nucleating factors and hypomotility of the gallbladder. The most important factor is the increased saturation of cholesterol in the bile. Cholesterol is mostly insoluble in water and its solubility depends on bile salts and phospholipids (such as lecithin) to form vesicles that have a hydrophilic outer surface, allowing cholesterol to be transported (Jessurun & Pambuccian, 2009). When the amount of cholesterol secreted exceeds the amount of bile salts and lecithin that are needed to make cholesterol soluble (due to increased activity of the ATP-dependent transporters on hepatocytes), precipitation and crystallisation of the excess cholesterol can lead to the formation of cholesterol gallstones, as seen in Figure 1 (Henderson & Yantiss, 2010). The presence of particular proteins (nucleating factors) in the bile can promote or inhibit the precipitation and crystallisation of cholesterol. Pronucleating factors include mucin glycoproteins, immunoglobulin G and aminopeptidase N (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005).

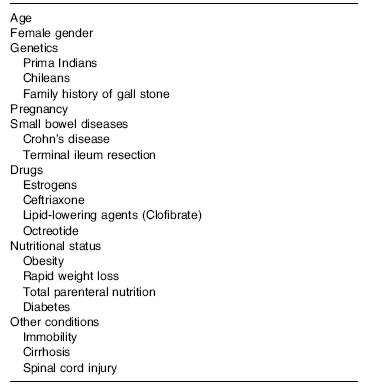

Table 1: Risk factors associated with the formation of cholesterol gallstones (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005)

The motility of the gallbladder is also involved in the formation of gallstones. Gallbladder hypomotility or stasis (impaired filling and emptying of the gallbladder) promotes the formation of cholesterol gallstones, by holding the cholesterol saturated bile static and allowing cholesterol to crystallise (Jessurun & Pambuccian, 2009). Some risk factors associated with cholesterol gallstones are outlined in Table 1. Females are at more risk of developing cholelithiasis (which may lead to acute cholecystitis) than men. This may be because of the effect that the hormones oestrogen and progesterone have on the formation of gallstones. Oestrogen promotes secretion of cholesterol causing supersaturation of bile, while progesterone decreases motility of the gallbladder (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005).

Clinical Features Symptoms and Signs: Patients with acute cholecystitis usually present with localised pain in the right upper quadrant, which may radiate to the right shoulder (Elwood, 2008). Associated symptoms may include nausea, vomiting and fever, with symptoms usually occurring after meals, while laboratory tests often show leukocytosis (Elwood, 2008). The patient may also show Murphy’s sign: pain and sometimes a sudden stop in inhalation when the gallbladder is palpated as the patient is asked to take a deep breath (Levy & Shah, 2011). Methods of Investigation: Ultrasound is the main imaging tool used to diagnose acute calculous cholecystitis (cholecystitis caused by cholelithiasis), with approximately 94% sensitivity and 78% specificity for cholecystitis (Levy & Shah, 2011). An ultrasound can show gallstones, wall thickening, dilation of the common bile duct, gallbladder size and pericholecystic fluid collecting around the gallbladder (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). However, ultrasounds can be restricted by factors such as obesity and bowel gas (Elwood, 2008). Alternatively, magnetic resonance imaging can be used, and has approximately 85% sensitivity for stones in the bile duct (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). General Approaches to Treatment: Treatment of acute cholecystitis usually begins with fluid resuscitation and administration of analgesia and antibiotics (broad spectrum), and may also involve making the patient ‘nil by mouth’ (Elwood, 2008). A cholecystectomy, removal of the gallbladder, is the standard method of treatment of calculous cholecystitis. A laparoscopic technique is preferred, as it causes less damage to the abdominal wall and results in a faster recovery time (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). An open cholecystectomy could also be performed, and in approximately 10% of cases, a laparoscopic cholecystectomy has had to be converted to an open cholecystectomy (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). Features Bearing on Prognosis: Laparoscopic cholecystectomies have been proven to be safe and effective, and result in a shorter hospital stay than open surgeries (Nejadnik & Cheskin, 2005). Previously, patients with acute cholecystitis were treated with antibiotics, and surgery was performed after the inflammation had subsided, sometimes weeks after the onset of symptoms. This is no longer the case as performing surgery early after the diagnosis of cholecystitis decreases the risk of complications (Elwood, 2008).

Reference List Elwood, D. R. (2008). Cholecystitis. Surgical Clinics of North America , 88 (6), 1241-1252. Henderson, J. T., & Yantiss, R. K. (2010). Non-Neoplastic Diseases of the Gallbladder. Diagnostic Histopathology , 16 (8), 350-359. Jessurun, J., & Pambuccian, S. (2009). Infectious and Inflammatory Disorders of the Gallbladder and Extrahepatic Biliary Tract, and Pancreas. In Surgical Pathology of the GI Tract, Liver, Biliary Tract, and Pancreas (2 ed., pp. 823-843). Levy, E. S., & Shah, K. H. (2011). Liver and Biliary Tract Disease. In V. J. Markovchick, P. P. Pons, K. A. Bakes, & 5 (Ed.), Emergency Medicine Secrets (pp. 248-254). Elsevier. Nejadnik, B., & Cheskin, L. (2005). Gall Bladder Disorders. In B. Caballero, L. Allen, & A. Prentice (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Human Nutrition (2 ed., pp. 384-389). Oxford: Academic Press.

|

|